This is the first article in the series.

The Gift of the Cognitive Revolution: Value as a Form of Collective Belief

According to ‘Sapiens’ by Yuval Noah Harari, what made Homo sapiens the most powerful species in the world is our capacity for storytelling—the ability to share ideas, even those that exist only in our collective imagination.

Forming communities has been crucial to human survival. Individually, we stand little chance against most wild animals. But as a community of 100 people, we become far more powerful than merely 100 individuals. This enables strategies and synergies that multiply our strength against threats. However, community size has a natural limit—around 150 people. Beyond that, maintaining cohesion requires more than just language and personal familiarity. This pattern is observable in family businesses, combat units, and even among chimpanzees. What allows us to transcend this limit is storytelling: the ability to create, understand, and share concepts that exist purely in our imagination.

This capacity for collective belief gave rise to communities, nations, religions, and systems of value. The gods of Olympus, for example, allowed strangers in ancient Greece to cooperate without knowing each other personally, united under a shared myth, or sometimes we call it culture.

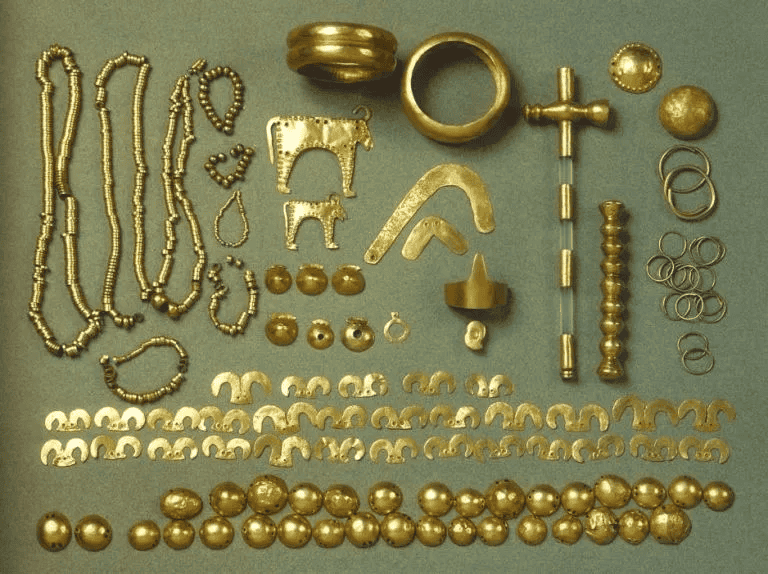

The formation of value systems is another product of this ability. We evolved from barter trade, which required a double coincidence of wants, to using mediums that serve as stores of value. That anchor of value is a consensus shared among different groups. Shells, pearls, jade, gold, and other physical objects once served as ancient currencies. These items had little practical use, yet became mediums of exchange because tribes collectively told a story: “rarity equals value.” However, such consensus was often regional. A shell from the Mesopotamian region would be seen as a meaningless stone in the Yellow River basin, simply because the two regions did not share the same “value narrative”.

Gold: The first ever universal symbol of wealth

The Epic of Gilgamesh, the world’s oldest known heroic epic, describes treasures such as a chariot “with wheels of gold and mountains of jewels.”

This “mystery of gold worship” perfectly illustrates Yuval Noah Harari’s idea: gold became a universal symbol of value not only because of its physical qualities (being rare, durable, and easy to divide), but also because humans built a “sacred story” around it that crossed cultural borders.

Some of the earliest uses of gold in ancient times were religious. Ancient Egyptians viewed gold as a divine, eternal substance and the flesh of the gods. In ancient Greece, Gold was considered a divine metal. The throne of Zeus, the staff of Athena and the floor of the palace of the gods in Mount Olympus were made of gold. The Roman Empire minted gold coins called Aureus, placing the emperor’s portrait on them, turning gold into an extension of power.

When different civilizations independently linked gold to ideas like holiness, eternity, and power, this shared “value story” broke through geographical limits. When Alexander the Great marched east, gold from the Persian Empire could be used alongside Greek coins without question. All along the Silk Road, from China to Constantinople, gold was the only “language of value” that needed no translation.

By then, gold was no longer just a metal—it had become humanity’s first globally accepted “imagined contract.” Whether you worshipped Zeus or Buddha, you believed this yellow metal could be exchanged for goods. This shared belief made gold the original “consensus asset.”

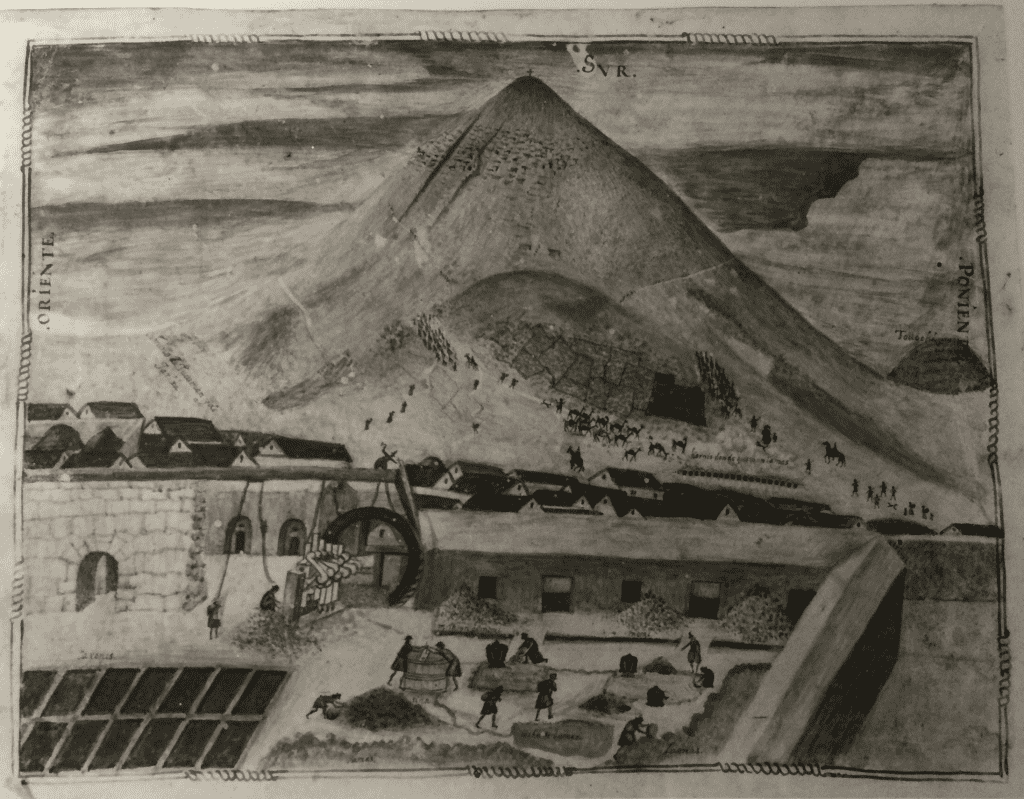

The Rise and Collapse of Silver: How Supply and Demand Shatter Consensus Value

The idea that “scarcity creates value,” which gold seemed to prove, was seriously challenged when the balance between supply and demand broke down. A classic example is Spain’s massive silver mining in the Americas during the 16th century.

When Spanish explorers discovered huge silver mines in places like Potosí (now in Bolivia) and Zacatecas in Mexico, they thought they had overcome the ancient problem of precious metal scarcity. Fleets of up to 100 ships regularly crossed the Atlantic, carrying around 170 tons of silver each year to Seville, Spain. One-fifth of this wealth went directly to the Spanish royal family. In the late 16th century, it funded up to 44% of the kingdom’s spending.

With this flood of silver, the Spanish “piece of eight” silver coin became the world’s second global currency after gold. It helped Spain pay for long wars in Europe and opened trade routes between Europe and Asia. Europeans used silver to buy silk from China and spices from India. For a while, silver was the trusted money used everywhere.

But this “easy wealth” didn’t make Spain rich forever. Instead, it created a trap—like the story of King Midas, who turned everything to gold but couldn’t eat it. When too much silver entered the market too quickly, even though people still believed in its value, the actual worth of silver dropped sharply.

This oversupply caused what historians call the “Spanish Price Revolution”—a great inflation that lasted between the second half of the 16th century and the first half of the 17th century. The price of basic goods like wheat, which had been stable for centuries, shot up. In England, where the best records exist, the cost of living rose sevenfold during this time.

Ironically, all that silver didn’t help Spain control its empire. It couldn’t stop the Dutch from rebelling or prevent England from breaking away. In the end, Spain was weakened by inflation and endless wars. The empire that silver built was also destroyed by it.

Shared belief is the foundation of value, but supply and demand are the key factors that keep that foundation stable. Even assets like silver, which was accepted by people all over the world, can lose their value if supply grows much faster than demand. The story that “rare means valuable” stops working.

Value doesn’t just come from belief. It’s the result of both shared imagination and balance between supply and demand.

When supply and demand become too unbalanced and pass a tipping point, even the strongest beliefs can collapse.

Diamond: A Modern Case Study in Shared Imagination and Supply Manipulation

If the value of gold can be described as “natural scarcity plus collective belief,” and the value of silver as “a consensus shattered by supply and demand,” then the diamond represents a more advanced form of value construction—it stands as the world’s first major example of a commodity whose shared imagination and supply-demand dynamics were both heavily manipulated, completely breaking from the traditional idea that value must rely on inherent natural attributes.

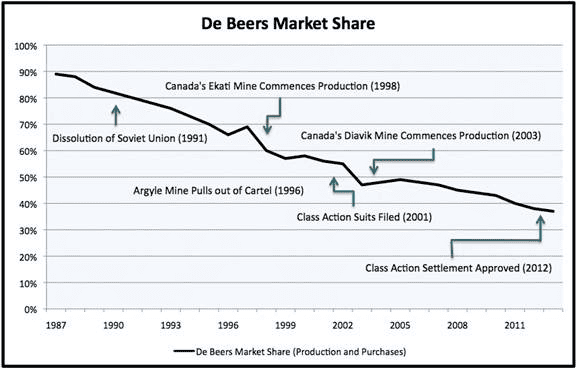

The “value story” of diamonds has been artificially constructed from the very beginning. In the early 20th century, De Beers monopolized global diamond mining, first controlling scarcity from the supply side—even though diamond reserves are geologically abundant (far more plentiful than gold), De Beers artificially created the illusion of scarcity by limiting output and destroying excess inventory. Then, through marketing narratives like “A Diamond Is Forever,” the company tied diamonds to the concept of “eternal love,” constructing a cross-cultural shared imagination: people believed in the value of diamonds not because they were inherently rare or useful, but because advertising told them that “diamonds symbolize love” and that “only a rare diamond is worthy of eternal love.”

A more sophisticated form of control lies in circulation: De Beers strictly limited the secondary diamond market by recycling old diamonds and suppressing resale platforms, avoiding the risk of value depreciation due to increased supply—a sharp contrast to the uncontrolled mining of Spanish silver. In this system of manipulation, the value of diamonds relies neither on natural scarcity (actual reserves are ample) nor on organically formed collective belief (diamonds were originally just ornaments for Indian royalty). Instead, it hinges on capital’s dual control over both imagination and supply and demand: first crafting a story that makes people want to believe, then manipulating supply so they have no choice but to believe (if you want to buy the “symbol of love,” you must accept the monopoly price).

This model marks a new stage in humanity’s ability to manipulate value: no longer passively relying on natural conditions or spontaneous consensus, but actively designing imagined narratives and precisely regulating supply and demand, turning value into a tool that can be shaped by capital. The essence of diamond’s value remains “fiction constructing reality,” but compared to gold’s “natural consensus” and silver’s “uncontrolled supply and demand,” it more extremely demonstrates the dominant role of human factors in shaping value systems.

Comparison with the Tulip Bubble & Recent Challenges of Diamonds

It is worth contrasting the diamond with another famous value phenomenon—the tulip mania of 17th-century Netherlands. The tulip bubble was a classic example of a speculative frenzy built almost entirely on collective delusion, with no underlying supply control. Tulip bulbs were relatively easy to produce and reproduce, and once market euphoria faded, the bubble burst dramatically precisely because supply could rapidly expand—there was no central entity restricting how many tulips could enter the market.

Diamonds, on the other hand, represented a controlled bubble—one sustained not by pure speculation but by deliberate supply management and narrative enforcement. For over a century, De Beers succeeded in maintaining high prices and perceived value through its monopolistic practices.

However, in recent years, this carefully constructed system has begun to weaken. The rise of lab-grown diamonds has introduced a disruptive alternative: chemically and visually identical to mined diamonds, but available at a fraction of the price. As consumers become increasingly aware that diamonds are not naturally rare—and that their “value” was largely manufactured—the shared imagination De Beers so carefully built is being questioned.

Moreover, the increased transparency brought by digital markets and resale platforms has made it harder to fully suppress secondary diamond trading. Although natural diamonds still hold symbolic and emotional weight for many, the myth of scarcity is fading. The diamond—once the ultimate example of supply manipulation—now faces a crisis of credibility, reminding us that even the most carefully engineered value systems are vulnerable when truth and alternatives emerge.

Conclusion: The Essence of Value Lies in Balancing Belief and Supply-Demand

From shells used in barter trade to globally circulated gold, from Spanish silver to naked fiat currency, and further to artificially manipulated diamonds—the evolution of humanity’s value systems has always revolved around two core variables: collective belief and supply-demand dynamics. The research of both Harari and Ferguson points to the same conclusion: at the heart of economic systems lies not material substance, but “belief constrained by supply and demand.” We believe shells have value, provided they are scarce within the tribe; we believe paper money has value, provided the government maintains supply stability; we believe diamonds have value, provided capital successfully manipulates both the “story” and the “supply.”

This ability to “construct reality through fiction” is both a glory of human civilization and a source of its fragility. The lesson of Spanish silver reminds us that belief which ignores supply and demand will eventually collapse. The case of the diamond, in turn, warns us that overly manipulated supply can also disintegrate when trust erodes — as seen today with the decline of De Beers’ monopoly and the rise of lab-grown diamonds, which are now shaking the very foundations of the diamond value system. Understanding the nature of value does not negate its significance. Rather, it allows us to see clearly that the key to sustaining value has never been mere “belief” alone, but the balance between belief and supply-demand. It requires both crafting a narrative worthy of trust and maintaining a baseline of supply stability. This is the insight history leaves us with — and the core logic that will underpin the operation of future value systems. This brings us to what may be the ultimate evolution of the diamond story: a deliberately enforced narrative, paired with fully transparent and decentralized transaction and ledger management, a coded supply with absolutely no behind-the-scenes manipulation—a tokenized common belief governed not by people, but by code.